I’ve been speaking about Azure AD + cloud identity a lot recently, mostly at DevCamps along the east coast (which, by the way, if you’re near one you should come spend the day with us — I’ll be in Raleigh 3/17 and Charlotte 4/1).

Identity is a massive topic and as such, trying to cover even a big bite of it within an hour is difficult. I think we all take for granted all of the ‘behind the scenes’ work that goes on in ‘traditional’ identity systems, like Active Directory Domain Services. In a completely controlled domain environment, AD gives us all we’d ever need for user authentication, much of which end users never see. The wonders of Kerberos!

Unfortunately, a lot of these pieces don’t really work over the internet, nor do they work in untrusted (e.g., non-domain-joined machines). Imagine trying to resolve the netbios name of your domain via DNS on your iPhone — something tells me ‘CORP’ won’t resolve, and even if it does, chances are it won’t be the ‘CORP’ you’re looking for.

So how do we maintain the same fidelity of user experience on non-domain joined devices? Let’s take a brief history lesson. Modern identity really isn’t all that modern at all, at least conceptually — most of the same functions occur, but the underlying implementations are different (and more visible to the end user).

Kerberos

We’ll start with a hyper-simplification of what Kerberos does.

I need a TGT (Ticket to Get Tickets), which I can swap out for a Service Ticket. That service ticket I then use to get more tickets for authenticating to resources. In addition, the service I’m attempting to authenticate to needs to know how to understand the ticket and can validate the ticket.

In Windows, this process is highly transparent to the user. When I sign into a domain joined machine, I’m getting my TGT. Generally the TGT is longer-lasting so I can continue to request service tickets. When the login process is spinning, part of what you’re waiting on is getting the TGT.

I found a rad image from the late 90s (I especially love that hot-pink starburst) outlining the back-and-forth between a PC, service + Kerberos KDC:

Kerberos circa 2000. Credit: MSDN

‘Modern’ Federated Identity

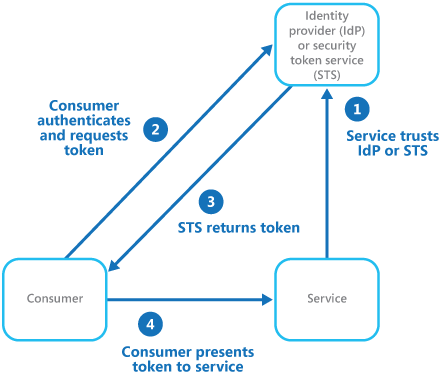

Now let’s look at a modern federated identity platform and how it works:

Federated Identity cloud design pattern. Source: https://msdn.microsoft.com/en-us/library/dn589790.aspx

In a federated identity system, we have a Secure Token Service that issues validatable tokens containing all of your claims (attributes — name, unique ID, UPN, etc). The service needing authentication is a Relying Party because it Relies on the STS for authentication. You, as the consumer, request a token (ticket) from the STS, which then in turn is used to authenticate to the remote service. The remote service trusts the STS and via a key exchange, can ensure the validity of the ticket. Sound familiar?

Trusted v Untrusted

So why does identity throw us as devs + IT pros completely off our game? Simple — until now, this process was almost completely transparent. Someone else had done all the hard work for us, mostly through NT/Kerberos. In a trusted environment, our machine is part of the domain so our machine authenticates and so do our users. In the untrusted environment (e.g., non-domain devices, the internet, etc), the entirety of the process happens over HTTP. HTTP is visible, because most users encounter it when they try to sign into a protected property. The remote web servers of SharePoint Online, for example, have no idea what I’m coming from, except that it’s an internet browser. There’s no intrinsic domain PC trust, there’s no visibility into that machine — so when a user tries to authenticate, these token swaps are going to happen, and the easiest way to do that with browser-based applications is by just sending the user from point-to-point in the authentication chain.

That’s why you’re going to see the Office 365 login page, followed by ‘Redirecting you to your organization…’ followed by your STS (like ADFS), before being redirected back into the target application. In a properly-configured environment, this should result in as-close-as-is-possible SSO experience.

What we’re really seeing here is modern identity platforms aren’t really all that modern at all — in fact, what makes them modern is merely the implementation (not that it is trivial, far from it, in fact) and the protocol used for communication is simply more visible to the end users.

I’ll have some more hands-on getting started around Azure AD soon.