I’ve been spending quite a bit of time in Tampa recently — most recently Cardinal’s first annual Innovation Summit for our Tampa service. I like flying to Tampa because the airport has been done just right — going from curbside to gate can routinely take only around 10–15 minutes, especially if you have precheck. Even this morning, when pretty busy, it was only about 10 minutes from curb to gate. Charlotte is always crazy and busy, but it’s generally efficient as well, especially with the volume of people going through there — but I think Tampa’s maximized their efficiency even more by putting more services closer to where and when they are needed or consumed (I think you see where this is going).

This got me thinking as I plodded through the airport (top tip: airports aren’t a good place to break-in new sandals), the application architectures that drive cloud efficiency are replicated in real-life all around us.

Let’s look at what typical major airports have to deal with:

- Large numbers of inbound and outbound traffic, for a variety of different (but known) tasks

- Many gates, capable of moving large numbers of people and planes in and out, spread out across…

- …multiple smaller, distributed buildings (airsides/concourses), with a small number of gates per building

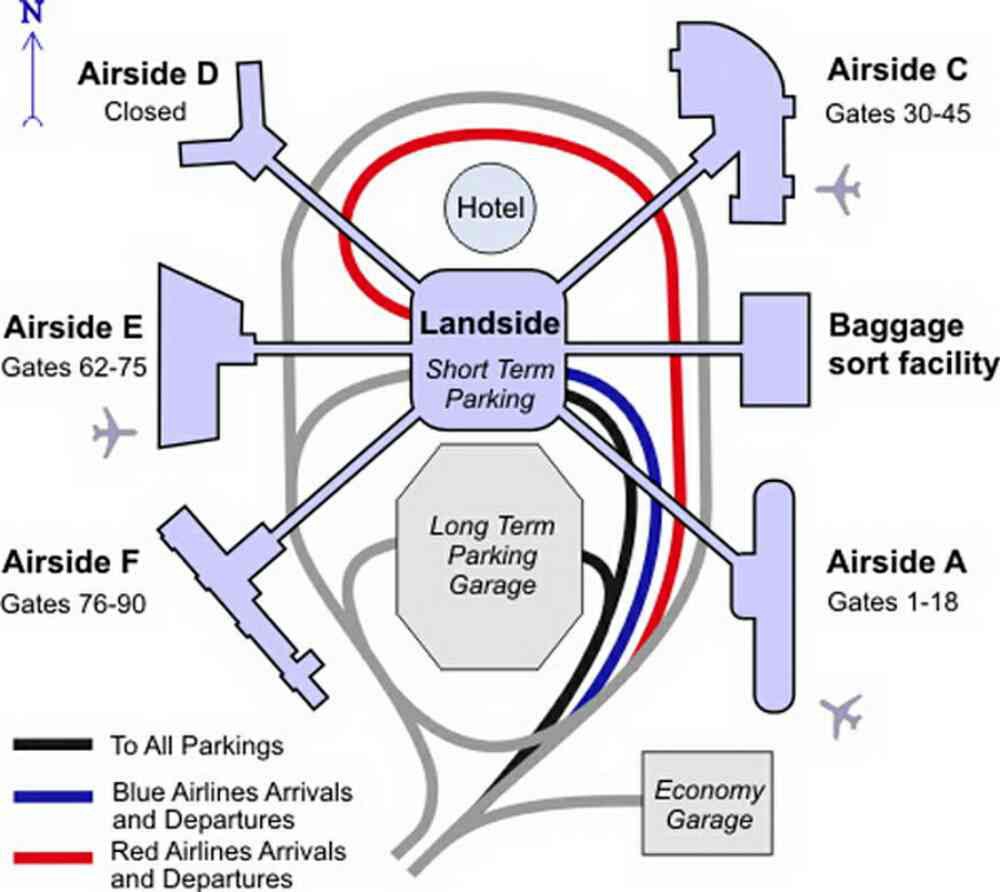

Here’s a map of Tampa, which shows this

Tampa International Airport — aviationexplorer.com

Tampa International Airport — aviationexplorer.com

Distributed Services + Pipes/Filters

And the services that are offered in each area (note, my numbers have been pulled completely and totally out of thin air, I have no idea what volume TPA does):

Main Terminal — ticketing, checkin, greeting spots, baggage claim, cars, cabs, etc. — 10,000 people/hour

People Carrier — only ticketed passengers — 2,000 people/hour

Airside — only ticketed passengers leaving from one of the serviced gates — 2,000 people/hour

Concourse — only ticketed passengers, who passed security, who are leaving from a specific gate at some point today — 1,500 people/hour

Flight — only ticketed passengers, who passed security, who are leaving from gate F84 at a specific time today — 126 people right now

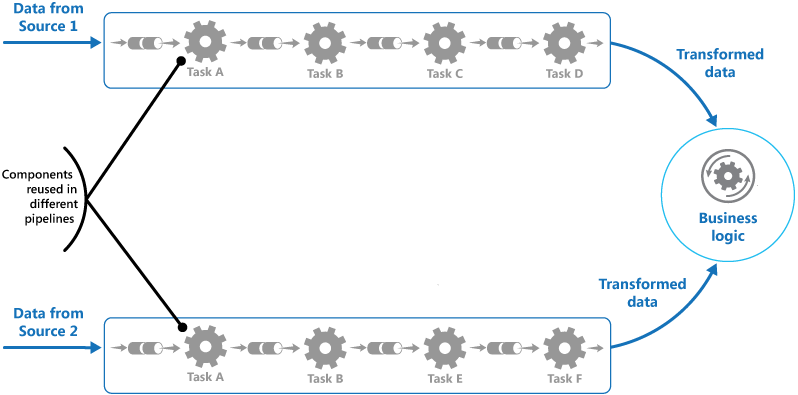

As you can imagine, by the time you get to your gate, you can say with relative confidence that everyone there is only leaving within a small time window from that gate. This is very similar to a pipes and filters pattern, where the same task is repeated over and over again, but the entire process is broken down into discrete steps, which, when executed, process data appropriately and route to the final destination.

Pipes & filters @ MSDN: https://msdn.microsoft.com/en-us/library/dn568100.aspx

Think TSA is slow today? Imagine if it processed every person through the airport, not just flying passengers. It would be a nightmare and horribly inefficient. By using multiple copies of the same service, closer to the consumer, you can distribute load across all of them, leading to significantly shorter wait times while still offering the same (or better) level of service.

Not only have we now distributed a high-transaction process, we’ve pushed it closer to the consumers and put it in a more efficient place in the workflow.

ID + Boarding Pass, Plz — Federated Identity

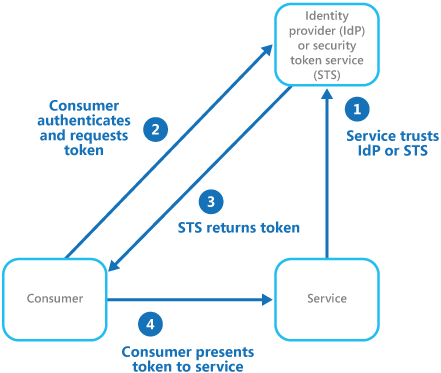

Anyone who’s ever heard one of my identity sessions knows I generally use an ID + bouncer at a club scenario to describe a federated identity system at work in the real world. This is no different.

In our airport case, upon arriving to the friendly TSA agent, I’m asked to produce some form of ID, plus a boarding pass. This combination of valid identity and time-sensitive token authenticate me to the agent, who then grants access to the terminal. The key here, however, is that the TSA agent has no idea who I am (well, at least I hope not). He (the relying party) relies (see how that works) on

- an external, trusted third party, like the Secretary of State, in cases of a passport, or NCDMV for a driver’s license to vouch for my identity (e.g., an identity provider),

- a known set of anti-forgery tools, like UV-sensitive watermarks, specific microprinting, encoded data, RFID, etc. to ensure the identity document is valid (e.g., a signature), and

- some data points, like my picture, name, hair color, height, departing flight time, etc to validate I have access to what I’m requesting (e.g., attributes or claims, depending on the consumer, the requested access is generally to a resource)

- In addition, my driver’s license is only valid in some situations, like ID validation within the US. This roughly translates to an audience, or which targets the ID document has been issued for. This is an important security consideration — if someone steals my driver’s license, they can use it for whatever to validate their (my) identity. This doesn’t work outside of the states, however, so it’s only useful to spoof identity within a specific region (e.g., the US), which is the only place that document is valid.

Our modern, federated identity patterns follow a similar pattern — a trusted third party acts as the identity provider and validator, which is what prevents me from having to have a TSA-specific ID. Since TSA trusts NCDMV and SoS, that trust is extended to verifiable documents I possess.

Your cloud app does the same thing — an exchange between identity provider and relying party establishes a trust and a public key; incoming data is then signed with the private key, which can be decrypted and verified with the public key of the IdP.

Federated Identity pattern @ MSDN https://msdn.microsoft.com/en-us/library/dn589790.aspx

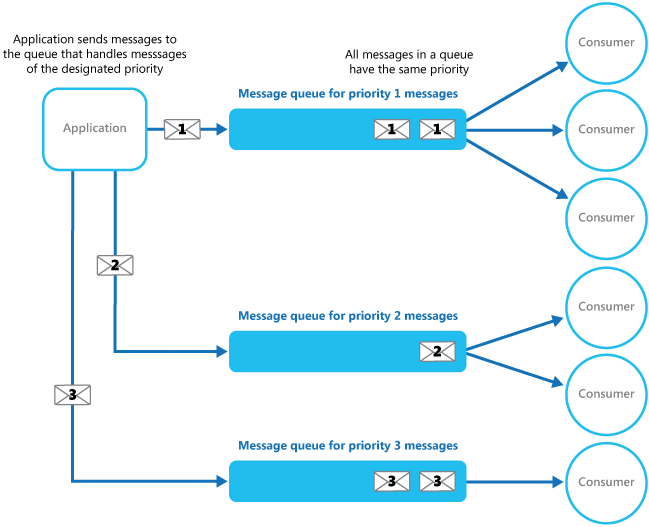

PreCheck? Preferred? SkyPriority? Priority Queuing

Last one for now. Notice how there are multiple security lines at the airport? TSA PreCheck, First/Biz Class priority screening, Clear card, Crewmember? Here we have people who, one way or another, are of a higher priority to process faster. They could have gone through more rigorous background checks in the case of TSA Pre, or paid more for a flight — either way, each of these people get access to a shorter line for processing (ignore for now that the processing logic of each of these people is also different — imagine we’re all going to the same generic black hole of security screening). These are priority queues — people in those queues are processed first, while standard people either wait in a longer queue, or in some cases, the same queue, but priority people get preference as soon as they arrive. You see this pattern all over airports — check-in, security, gate.

In some cases, priority people have entirely separate queues with a shared TSA agent. In this case, as soon as the priority passenger arrives, the shared TSA agent pauses processing the standard queue to process the priority passenger. Once the priority queue is full, that agent starts working the standard queue again.

In other cases, priority queues have dedicated processors reading those messages. This is closer to the check-in process, where dedicated check-in lines lead to dedicated check-in agents processing first/biz class passengers.

Lastly, we have the gate — first class first, then biz, then the unwashed masses. This is a single queue that calls on specific classes of messages to enter a queue at a specific time. This pattern is the least common of the priority queuing patterns seen in software and is generally used for managing messaging to a legacy system or something which requires specific processing order. You’ll usually see some other processing logic elsewhere that places messages in the queue at a specific time to ensure priority.

Anyway, your code can follow a lot of these patterns as well — for critical messages, perhaps you use a dedicated queue and dedicated processor. These messages are guaranteed to be processed nearly immediately. As soon as the dedicated processor is done with each priority message, it dips back to the queue for the next priority message.

Similarly, for priority-but-not-critical messages, or for priority messages that are rare, shared processors can check the priority queue before doing any standard queue processing. This allows for priority message processing, but not critical, real-time message processing. For example, if your worker is working on a long-running standard message, your priority queue item may wait before being processed, but would be guaranteed to be next in line.

Simple priority queue processing @ MSDN https://msdn.microsoft.com/en-us/library/dn589794.aspx

Start Looking Around…

…and you’ll see a lot more patterns. There are more we could dig into just in an airport and all kinds of other scenarios. These cloud patterns make sense because they’ve been proven across the world in all sorts of physical incarnations — why reinvent the wheel if you don’t need to?

I hope this helps connect a few of the dots — as always, feel free to drop me a line or ask a question.