Mobile services. MVC Web APIs. They’re all over and ubiquitous now. In some cases though, WCF is still the platform of choice for service developers. Sometimes it’s interoperability with other services, sometimes it’s just not wanting to rewrite old code — or perhaps a large part of your architecture requires service hosts + factories — whatever the reason, it’s not feasible to rewrite or rearchitect large swaths of systems just to add authentication.

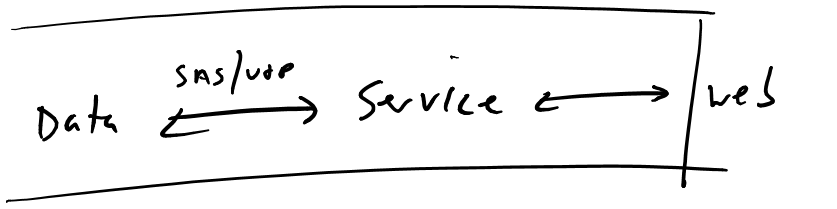

Typical, 3-tier Apps

Let’s look at a typical three-tier app — UI, service + data:

Firewalls keep everyone out except our web app.

Here, we’ve got a web app which talks to an unauthenticated service, which talks to some data. Pretty simple stuff. The box indicates the internet permeability — if the web server is the only thing exposed to the internet, this is a generally OK approach. If nothing has access to the service except the target consumer, what could go wrong? How hard could it be?

In this model, your web app is handling authenticating clients, which then proxies requests back to the service. A pretty standard model.

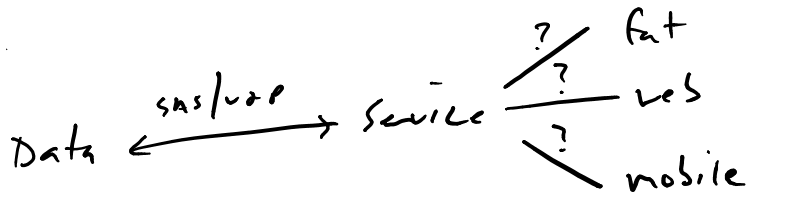

Tomorrow

But let’s extrapolate further. It’s 2015 — how many services only have a single web client anymore? Everything is connected and everything is slurping data from everything else. Not only are we going to have trusted hosts, we’re going to have mobile apps, perhaps we expose an API — there are lots of things to consider. Here’s how I’d expect our app to look from a modern looking glass:

[caption id=”attachment_356” align=”aligncenter” width=”808”]

Our service now has to handle multiple clients — and they’re not all coming from a trusted host.[/caption]

Our app has to handle some number of potentially unknown entry points.

So what are we to do? We can leverage OAuth server-to-server to secure our services. This way, we’re not publishing a static key into our mobile applications — as anyone who’s seen how trivial it is to decompile an Android app knows, you can never trust the client. There are two options — we’re going to dig into the first (application-only, 2-legged OAuth) — and we’ll follow up with 3-legged in a later post.

Server-to-server OAuth (e.g., 2-legged, Application-Only)

Our first option is:

- significantly better than no authentication

- somewhat better than static keys/shared credentials

- useful for locking-down an API, but not necessarily at a user-level

This is application-only access, also known as two-legged OAuth. In this model, the server doesn’t need to know a specific user principal, but an app principal. A principal token is required by the service and is requested by the client:

- STS-known client requests an OAuth token from STS (e.g., Azure AD)

- STS-known client sends token in header (Authorization: Bearer eQy…)

- Service expects header, retrieves token

- Service validates token with Azure AD

User OAuth (aka 3-legged)

This option is somewhat different — instead of using an application prinicipal to connect to our service, we’re going to be connecting on behalf of the user. This is useful for:

- applications that rely on a service to security-trim data returned

- services that are public or expected to have many untrusted clients

In this model, users authenticate + authorize the application to act on his/her behalf, issuing an access token upon successful authentication. The application then uses that token for requesting resources. If you’ve ever used an app for Facebook or Twitter, you’ve been through a 3-legged OAuth model.

Update 1/6: Bindings

It’s worth mentioning here that we’re not really relying on WCF to do anything here, short of using the filter + behavior. Because of this, the binding I’ll be using is a standard BasicHttpsBinding. Think of it as using application-level authorization instead of relying on an IIS or hosting filter in a binding.

WCF Service Behaviors + Filters

There are two pieces we need to build — a server-side Service Behavior that inspects + validates the incoming token, and a client-side filter that acquires a token and stuffs it in the Authorization header before the WCF message is sent. We’ve used this pattern on a few projects now — this is a good resource for more details and similar implementations.

We need to do three things:

- Update the WCF service with a message inspector that will inspect the current message

- Update the WCF client to request a token and include it in the outgoing message

- Update the WCF service’s Azure AD application manifest to expose that permission to other Azure AD applications

Service Side

Service side, we want something which can inspect the messages as they come in; this inspector will both grab the token off the request + validate it. This started life from the above blog post, but was modified for the newer identity objects in .net + WIF 4.5 and for clarity.

Some Code

Looking through here, we’ll find pretty much everything we need to make our WCF service ready to receive and validate tokens. The highlights:

BearerTokenMessageInspector.cs

Here we’re doing the main chunk of work.AfterReceiveRequest

is fired after the WCF subsystem receives the request, but before it’s passed onto the service implementation. Sounds like the perfect place for us to do some work. We’re starting by inspecting the header for the Authorization header, finding the federation metadata for that tenant, and validating the token. System.IdentityModel.Tokens.JwtSecurityTokenHandler

does the heavy lifting here (it’s a NuGet package), handling the roundtrips to AAD to validate the token based on the configuration. Take note of the TokenValidationParameters

object; any mis-configuration here will cause validation to fail.

BearerTokenServiceBehavior.cs

Next we’ll need to create a service behavior, instructing WCF to apply our new MessageInspector to the MessageInspector collection.

BearerTokenExtensionElement.cs

This is a simple class to add the service behavior to an extension that can be controlled via config.

WcfErrorResponseData.cs

This is a helper for returning error data in the result of a broken authentication call. We can return a WWW-Authenticate header here (in the case of a 401), instructing the caller where to retrieve a valid token.

Service Configuration

The last piece is updating the WCF service’s config to enable that message inspector:

Client Side

Now that our service is setup to both find and validate tokens, now we need our clients to acquire and send those tokens over in the headers. This is much simpler, thanks to the ADAL — getting a token is about a five-line operation.

AuthorizationHeaderMessageInspector.cs

The AuthorizationHeaderMessageInspector runs on a client and handles two things — acquiring the token and putting it in the proper header.

AzureAdToken.cs

This is a simple helper for acquiring the token using ADAL. You can modify this to pop a browser window and get user tokens, or using this code, it’s completely headless and an application-only token. ADAL also handles caching the tokens, so no need to fret about calling this on every request.

AuthorizationHeaderEndpointBehavior.cs

A wrapper to add the AuthorizationHeaderMessageInspector to your outgoing messages.

EndpointExtension.cs

A simple extension method for adding the endpoint behavior to the service client.

Usage

Wrap it all together, here’s what we’ve got — a simple call to ServiceClient.Endpoint.AddAuthorizationEndpointBehavior() and our client is configured with a token. Your call out should include the header, which the service will consume and validate, sending you back some data. Easy, right?!

Configuring Azure AD

The last thing we need to do is configure Azure AD with our applications. Those client IDs and secrets aren’t just going to create themselves, eh? I’m hopeful if you’ve made it this far that adding a new application to Azure AD isn’t taxing your mental resources, so I won’t get into how to create the applications. Once they’re created, we need to do two things — expose the permission and grant that to our client. Let’s go.

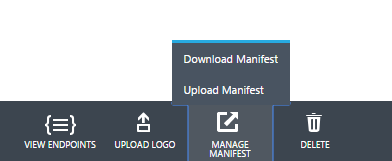

App Manifest

The app manifest is the master configuration of your application’s configuration. You can access it via the portal, using the ‘Manage Manifest’ in the menu of your app:

Download your manifest and check it out. It’s likely pretty simple. We want to add a chunk to the oauth2Permissions block, then upload it back into the portal:

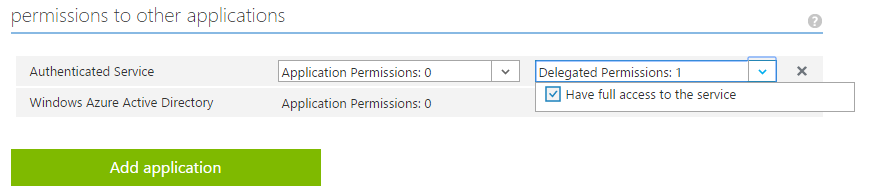

What’s this doing, exactly? It’s allowing us to expose a specific permission to Azure AD, so we can grant that permission to other Azure AD applications. Head over to your client application’s Azure AD app record. Near the bottom of the ‘Configure’ section, we’ll see ‘Permissions to other applications’ — let’s find our service in this list. Once you’ve found it, you can grant specific permissions. Extrapolate this further, and you can see there’s certainly room for improvement. Perhaps other permission sets and permissions are available within our app? They can be exposed and granted here.

Ed note: It’s finally out of preview!

It’s a trap wrap

What you’ve seen is a ready-to-go example of using Azure AD to authenticate your applications. We’ll dig into using user tokens at both the application and service levels in a later post, but in the meantime, you’ve now got a way that’s better than shared credentials or *gasp* no authentication on your services.